It was spring when the stranger found me. I watched him as he stumbled over the roots of the great oaks that had grown to obscure the once-pristine path that led to my gate. I couldn’t help but stare. I hadn’t seen one of his kind since Lord Asenger and his family roamed my halls. I watched as he yanked his worn traveling cloak from the grasp of a sapling’s longing, outstretched limb.

He opened my gate slowly. The hinges hadn’t been put to work in many years, and their atrophied bodies screamed in rebellion. I felt a sharp, electric pain as rusted metal scraped against rusted metal. The stranger only opened my gate enough to allow him passage and slipped through the slight opening.

A shiver ran through my body. I felt his boots on the grass, could hear his sigh as he leaned against my wall. He stared at me. I stared back. I could feel his eyes picking me apart, taking in every detail. They traveled from bay to buttress, taking in the intricate craftsmanship of my spires and the ornate stained glass that peered into my great hall. The stranger’s eyes absorbed every shingle on my many slanted roofs, every stone of my austere walls, every pane of my dark, lifeless windows.

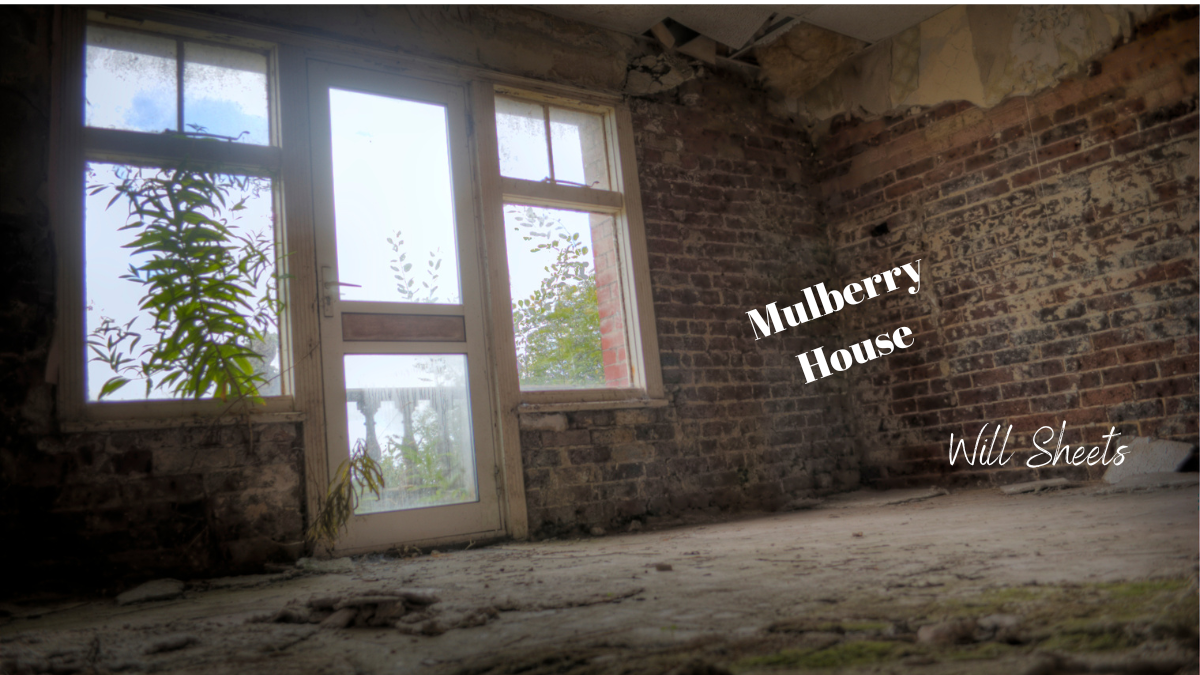

I felt a sudden stab of self-consciousness about my current derelict state. I hated that the stranger could see the cobwebs hanging above my grand front door. I hated that the grass of my once perfectly maintained grounds was tall enough to brush the stranger’s thighs. I hated the moss that grew over my walls. Most of all, I was ashamed there was no one here to welcome him.

As the stranger watched me, he reached to his right and, without looking, pulled a weed that had grown between two stones in my outer wall and tossed it over my gate. I shuddered. The weed had irritated me since the first buds of spring began to adorn the trees. Under the Asenger’s watch, gardeners would never have permitted the weed to stay, but in their absence, the irritant had grown and festered. I had gotten so used to its constant annoyance. I was so surprised by the weed’s absence I almost didn’t notice the stranger pushing open my front door and walking inside.

The stranger settled in quickly. He spent the first few days wandering my halls, exploring the rooms, hallways, balconies, and crawl spaces. His lust for exploration was seemingly endless.

He would spend hours roaming, leaving footprints in the thick layers of dust that coated my floors. The stranger had a knack for finding his way into whatever space he wanted. In addition to the rooms and chambers that comprised the majority of my body, the stranger stumbled across cupboards and closets that even the Asengers didn’t know I possessed.

At first, the stranger’s constant wanderings frightened me. They seemed invasive. It scared me that this man, a man I had never seen before, could unravel all the mysteries I held. He could pull back the layers of time that hung in the air just as oppressive as the dust on my floors.

But I soon began to appreciate the stranger’s wandering. I began to feel a thrill every time he unearthed some new secret. I waited with bated breath for him to come across some long-unused crevice, hidden away among my many corridors. The stranger’s strides stirred the dust from my carpets. His presence in a room gave it the glow of new life as if he was meant to be there. As if I was made just for him.

The stranger slept in my master bedroom. He lay under the gilded awning that covered the luxurious four-poster bed, staring at the canopy for hours. I could tell from his breathing when he finally fell asleep. It was a trick I learned from Lady Asenger. She had spent many a night staring at the same canopy, breathing the same quick breaths as if sleep was determined to elude her. Or if she was determined to elude it.

Lady Asenger liked to pace when she couldn’t sleep, a habit the stranger was also prone to. I could feel his footsteps tracking back and forth over the once-resplendent red carpet that lined the floor. It had faded from a striking ruby to a dull maroon. It reminded me of the expensive mulberry wine Lord Asenger’s heir, Cyrus, was partial to. I began to worry that the stranger’s pacing would wear holes in the derelict carpet.

On the second night since the stranger came to me, I saw him cry for the first time. He lay in that beautiful bed and wept. My heart ached for him. I wanted to ask him what plagued him so, and what I could do to alleviate his pain, but gaping doorways are poor mouthpieces, and stone walls do not lend themselves to tender embraces.

The third day after he arrived, the stranger explored the servant’s quarters. He had located my pantries on the first day of his arrival and had fed himself from the stores of preserved jams and dried fruits they possessed, but the rest of the servant’s quarters remained untouched by his presence. He moved through the kitchens, sending a fleeting glance at the long-untouched stove tops and dusty pans. His gaze lingered on the knife block. The stranger pulled a few of the knives out and after testing their weights, slipped a long carving knife into his belt.

The stranger breezed past the various closets and storage rooms scattered throughout the servant’s halls, dispersed between sleeping quarters. However, the sleeping quarters themselves drew special attention. He stood, leaning against the doorways, peering into every cramped, four-person room. Many beds lay unmade, untouched for years, dust covering them like yet another blanket.

The stranger observed the clothing scattered on the floor of the rooms. He stared at the decrepit remains of an apple sitting beside one of the beds, put aside to enjoy later but never returned to. In every room, the stranger stopped and looked for personal items. He found many. The servants hadn’t had a chance to pack their meager possessions before being forced out. The rebels hadn’t bothered to remove them.

The stranger picked up a small stuffed bear lying on the pillow of a servant’s bed. He stared at the bear for a long time, feeling the thing in his hand, turning it over again and again. He moved on but kept the bear with him, tucking it into his belt on the hip opposite the knife.

He found more personal effects that seemed to enthrall him. A crumpled handkerchief, intricately stitched. A wooden cross on a string. A blue ribbon. The stranger returned to the master bedroom, the room I was beginning to think of as his, laden with remnants of people whose names have been long forgotten. Forgotten by all but me.

I remembered Leon, the cook whose loving grasp had worn the handle of the knives in the kitchen. I remembered Diane, who stitched handkerchiefs made of rags with as much care as she gave to Lady Asenger’s gowns.

I remembered Henry, the young man who cringed at the sight of the Asengers’ lavish dinner parties. I remembered the way he slowly pulled my doors open at night on his secret trips into town, believing he was doing the work of God. I remembered the horror on his face when the rebels slaughtered the Asengers’ guards in the uprising, leaving them slumped against the walls in the exact places he said they would be stationed. I remembered little Augus and the way he cried when the townspeople frog-marched the servants out my gate. I remembered how he begged his mother to go back for his bear.

I remembered Lyra, who always tied her hair up with a blue ribbon to keep it out of her way when she did the laundry. I remembered that the ribbon always had a way of making her eyes stand out. And I remembered the way those eyes welled with tears as she held Cyrus’ dying body. I could never forget the revulsion I felt when his blood pooled on my floors and stained his gorgeous ruby coat the color of his favorite mulberry wine.

The stranger placed the bear on what used to be Lord Asenger’s writing desk. He stood staring at it for a long time as the sunset shone through my windows. He wept again that night. I wished I were flesh and blood so I could weep too.

When he wasn’t exploring my grounds, my stranger spent many hours in my great hall. It was my largest room and the first thing anyone saw upon opening my grand oak doors. Lord Asenger had lovingly decorated the room with priceless art pieces and antiquities. It was his way of daunting visitors, an opulent gateway into the luxurious life of the Asenger family.

The grandeur of the hall had been significantly decreased as a result of the uprising. The rebels had torn the room apart while the Asengers fled, destroying countless priceless pieces. Peasants and farmers had no need for such luxuries, so the detritus lay scattered in the hall where it had lain for years.

The destruction of the hall was the most painful part of the uprising. Every moment I spent gazing upon the wreckage of the once beautiful hall reminded me of the love and care that had gone into making the space beautiful. Making me beautiful. And the dusty, forgotten remains of the tarnished masterpieces adorning the floor told me I would never find that beauty again.

My stranger loved the room as well, albeit differently from Lord Asenger and I. Where he had loved it for the wealth and power it symbolized, and I loved it for the care and effort it was created with, my stranger loved the hall for its mystery.

He moved between toppled columns and crumbled statues, sparing a moment to examine each bit of stone. He gazed at vandalized paintings with a furrowed brow. His attention seemed to give the dilapidated hall a new purpose. My walls nearly trembled with excitement when he unearthed pieces he had never seen before. New excitements for him, old memories for me.

There were a couple of pieces in the room that I deemed to be my stranger’s favorites. A small statue of a knight sitting astride a gallant mare always drew a wistful smile to his face. The regal knight’s left arm was missing, and the statue lacked a base, but it remained relatively whole by the hall’s standards.

My stranger was also very fond of a landscape that depicted me and my grounds in vibrant detail. I had always thought of it as my self-portrait. My stranger had dusted off the canvas carefully upon discovering the work face down near my hall’s grand doorway. The frame was splintered in two places, but the painting itself remained unharmed. He had placed it gingerly on a pile of rubble near the center of the room. My stones ached with happiness.

While I would like to say my self-portrait was my stranger’s favorite piece, it was clear there was another he preferred. The painting the stranger seemed so fond of was in worse condition than any other in the hall. It was a portrait of the Asenger family dressed in formal regalia. Lady Asenger sat on a finely upholstered chair, her hair flowing over her shoulders in dark waves. Her husband stood proudly behind her, his hand resting on her shoulder. A young Cyrus sat on Lady Asenger’s lap, hands crossed daintily, the perfect image of an obedient son.

The painting had been vandalized in the uprising. The entire family had been defaced, great gashes rent in the canvas. Without prior knowledge, it would be impossible to tell who the subjects were. The words “Finally, we can all eat” had been haphazardly written in dull orange paint in the bottom left corner of the portrait.

My stranger had spent hours looking at this painting. He took in the gentle way Lady Asenger held her son, the proud way Lord Asenger stood. He watched the painting like he believed the people in it were about to move. He watched the gashes where the faces used to be with a special intensity. He didn’t know what the Asengers looked like. I wondered what faces he saw instead. Sometimes when the stranger stared at the portrait, his eyes filled with tears. Sometimes he even let them fall.

Some part of me believed my stranger would live with me forever. The most delusional ideas are always the prettiest. They came for him seven days after his presence first graced my halls. I saw the men, a group of twelve, marching through the great, overgrown oak trees that had once lined the path so neatly. They moved uniformly with the practiced ease of professional soldiers. The noon-time sun glinted off their polished helmets and wicked halberds. A man dressed in the garb of a simple farmer was being shoved along in front of them.

My first reaction was one of excitement. My stranger had already blessed my halls with his wonderful, invigorating presence and how lucky was I that I might be the home of even more interesting visitors? Perhaps these new strangers might know my stranger?

The excitement dissipated quickly. As I watched the new strangers draw closer, watched one of the men with a halberd converse briefly with the peasant, pointing in animated fashion at my gate, I also kept watch over my stranger, who was paging through Lady Asenger’s diary in his bedroom. As soon as he heard the men’s gruff voices, he rushed to the ornate window on the wall opposite the bed. His face turned bone-white.

My stranger dropped the diary on the frayed rug which still reminded me of Cyrus’ wine-stained lips. And of his blood-stained coat. My stranger snatched the knife he had found in the kitchen from where it lay on the writing desk, slid it into his belt, and ran for the door. He stopped, hand resting gently on my door frame. I felt the new strangers open my rusted gate, forcing it wide, hinges screeching in protest.

My stranger dashed back to the desk and picked up the old teddy bear. He shoved it next to the knife and ran. The fear that had been steadily growing in me since I saw the pale sheen of my stranger’s face reached a crescendo. My stranger pelted through my halls. The men burst through my doors, slamming the fragile oak wood into my walls. The pain was immense, but I had no mouth with which to scream.

My stranger careened into my great hall. He froze. The new strangers called out, commanding him to remain where he was. My stranger tried to run. He wasn’t fast enough. The soldiers swarmed into my great hall, every footfall a phantom ache in the heart I didn’t have.

They caught him next to the statue of the knight on horseback. My stranger tripped on a piece of rubble, one of many scattered throughout the hall. The men swarmed him. I watched as they held him down. I watched as he was murdered. There was nothing I could do except watch and remember. I could not cry. I could not scream. I could not help. I could not tear the men off my stranger, could not expel them from my grounds, could not forbid them from setting foot inside my gate again. But I could watch. I could bear witness to my stranger’s last beautiful moments.

I can still picture every detail of his proud, regal face. I remember how his blood pooled on my floors, just like spilt mulberry wine. I will stand for generations, bearing with me the memory of Lord and Lady Asenger, of Cyrus, and of my beautiful stranger.

“I told you lot there was something wrong about that place! You can’t tell me you didn’t feel it.

“Aye, it was a bit odd, I’ll give you that.” As Capitan Dorset said this, he counted thirty pieces of silver into his informant’s hands. The man’s eyes shone nearly as much as the coins.

“Thank you kindly sir,” the farmer said. “It’s much appreciated!” As the man scampered off down the overgrown path, Dorset let out a sigh. It’s men like those that cause the most trouble. The kind of men who’d sell their own mother if the price was right, and with a smile to boot.

Dorset nodded at one of his men, a skilled archer by the name of Albren. Albren knocked his bow and pulled back on the string. It was a perfect shot. The farmer didn’t even have a chance to scream before the arrow took his life. He fell to the ground face first, his body obscured by the rough underbrush.

The captain signaled his men once more. They gathered their gear and began to march. The prince was dead, joined with the rest of the royal family in the grave. The coup was complete. Their job was done.

Dorset led his men through the mess of tall grass and snarled oak roots that blanketed a once-neat pathway. None of the men spared the farmer’s limp body a second glance. As the men marched, Dorset couldn’t help but look back at the old stone manor. He hadn’t lied to the farmer, the house did unnerve him.

He was not a superstitious man, but even so, a shiver danced up his spine as he took in the derelict mansion’s forlorn silhouette. A strong gust of wind rippled the captain’s uniform. The house creaked and moaned in the stiff breeze. Dorset thought it sounded a bit like crying.

Will Sheets is a seventeen year old high school senior who wants to study creative writing. This is his first story. Flora Fiction is happy to support first time writers. Will appreciates you all reading his work.

Comment